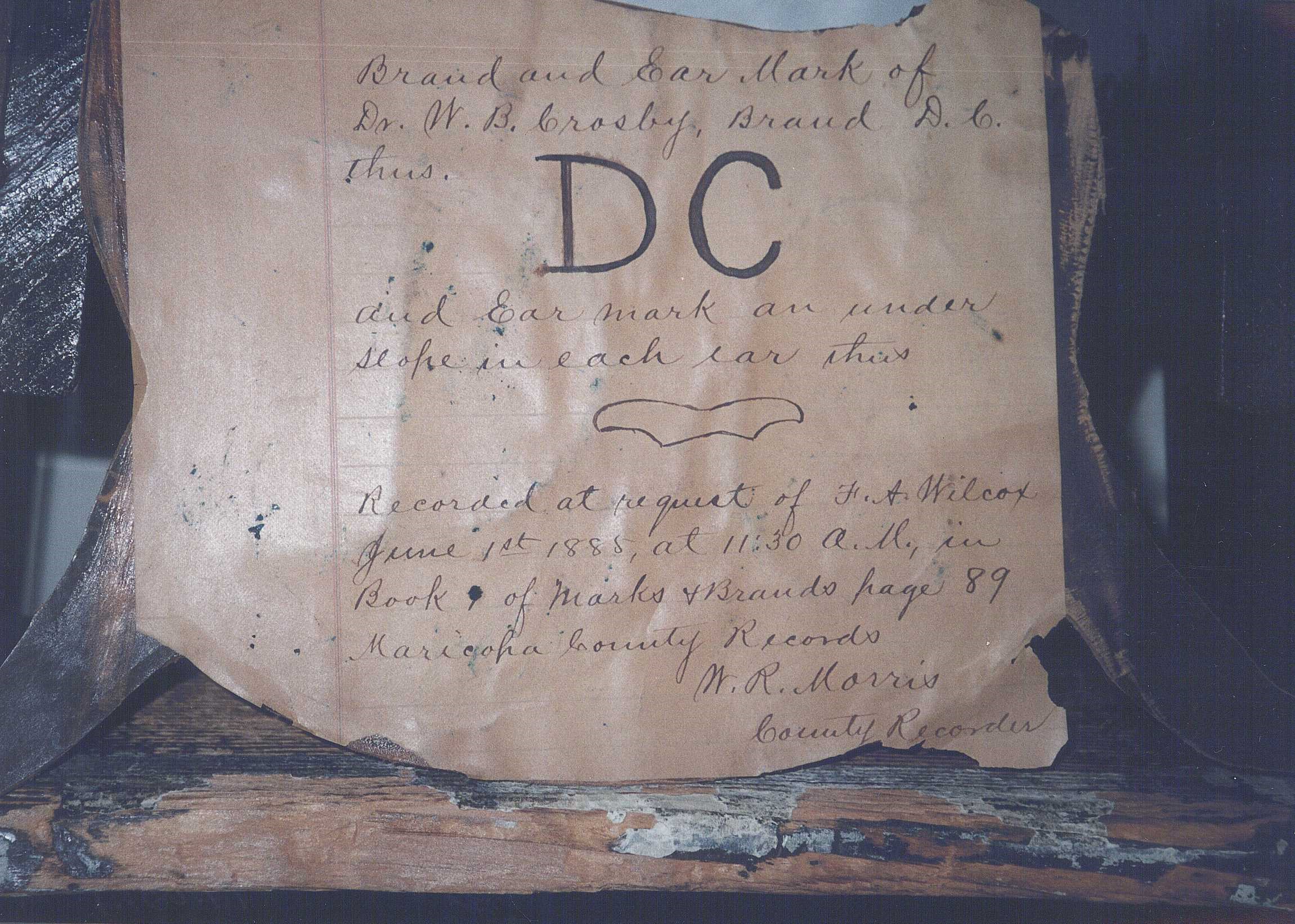

by Len Marcisz, McDowell Sonoran Conservancy Legacy steward Originally published in the Fall 2020 edition of Mountain Lines The McDowell Mountains are not the most famous mountains in Arizona, nor even in Maricopa County, where the Superstitions and their associated legend of the Lost Dutchman Mine draw international curiosity. But mountains, like people, don’t need to be famous to be interesting. Our McDowells have their share of myths, mysteries, legends, spooks, and curious happenings. In March 1972, Scottsdale City Parks and Recreation Director L. B. Scacewater issued an unusual plea to pilots flying in the vicinity of Scottsdale Airport. He requested their help locating the base camp of an elusive “old-time prospector” seen leading a pack animal in the McDowell foothills. Per Scacewater, picnickers reported seeing a “shadowy figure” but were unable to get near enough to identify either the man or the animal. “Oldtimers” living near the McDowells theorized that the mysterious prospector might have been seeking the Lost Dutchman Mine. Scacewater later concluded that either the prospector was a “figment of the imagination” of the picnickers or a local engaged in unauthorized mining activity. Subsequent to the initial reports, the “elusive” ghost was never seen. Did you know that there is a prominent feature in the McDowells that cannot be named on U.S. Geological Survey maps because its namesake, rather than being a ghost, is very much alive? At an elevation of 3925 feet, Tom’s Thumb is a rock climber’s paradise. First ascended on September 19, 1964, by local mountaineer Tom Kreuser, the granite outcropping cannot be officially named for him because the U.S. Board of Geographical Names does not honor living persons. No doubt Tom is in no hurry for the official recognition. There might be ghost cows at Brown’s Ranch. At least that has been suggested by Lynn Kelley, owner of Summerwind Marchadors. A lover of the McDowell Sonoran Preserve, she emotes on the quality of the Whiskey Bottle and Bootlegger trails and urges equestrians to ride the trails because “there are lots of stories about ghost cows at Brown’s Ranch—your horse may see one on the trails here!” McDowell Sonoran Conservancy stewards have not reported ghost cows in the area. Perhaps Marchador steeds retain a keener spiritual awareness. Brown’s Ranch does, however, have some eerily coincidental history surrounding its principal cattle brand, the DC, from which Scottsdale’s development DC Ranch takes its name. For many years, local historians erroneously attributed the creation of the DC brand to a Doc Crosby, or Doctor William B. Crosby—a person who never existed. The Brown family further mythologized the origin of the brand by maintaining that it stood for Desert Camp or Dad’s Cows. Some years ago, the Conservancy’s PastFinder stewards discovered the real Doc Crosby—but that was only the beginning of a spooky set of coincidences.  The real Doc Crosby was a military surgeon, William Dorr Crosby, who served at Fort McDowell during 1884–1886. He registered the brand but never used it because he was transferred to another military post. Crosby attended Beloit College, a small school in Beloit, Wisconsin, located in Rock County. Crosby’s brand changed hands over the years and was eventually acquired by E. O. Brown in 1917. Brown had come to Scottsdale from Janesville, Wisconsin, in 1904. Janesville is located less than seven miles north of Beloit in Rock County. Upon E. O. Brown’s death, ownership of the DC brand passed to one of his sons, E. E. Brown. E. E., needing financial support, acquired a business partner, Kemper Marley, who eventually acquired sole rights to the brand. A close associate of Marley’s was convicted of organizing the bombing assassination of Arizona Republic reporter Don Bolles in 1976. Bolles had been investigating Marley’s associations with politicians and criminal elements. The Bolles murder drew national attention to political graft in Arizona. Although Marley, a prominent Arizona businessman, was never indicted for the murder, public opinion reduced him to pariah status. As his business holdings were liquidated over the years, the DC brand eventually found its way to the development company of DC Ranch. And what of the murdered Don Bolles? He is memorialized today as an honored alumnus at his alma mater—Beloit College. In one of those strange manifestations of historical coincidence, the DC cattle brand came to be created, owned, and eventually ended, over a period of a century, while passing through the lives of three individuals from the same small county with a small private college 1700 miles from the McDowells. There’s a ghost that runs through Brown’s Ranch. It is not a cow; it’s a military road. The Stoneman Road, constructed in 1870, marked the first U.S. use of what is now Preserve land during the Westward Expansion. It was an Army supply route that ran through the pass between Brown’s Mountain and the low butte north of it. The military presence it brought allowed mining to flourish along its route from Cave Creek into the Bradshaw Mountains. It became one of the first major commercial roads in the region. Much of the road here fell out of use and disappeared with the closing of Fort McDowell in 1890. Prior to the summer of 1870, soldiers at Camp McDowell on the Verde River traveled a 175-mile route in order to reach military headquarters at Fort Whipple, near the town of Prescott. The indirect network of roads that constituted that route ran southwest from Camp McDowell, along the Salt River, through Phoenix, to Wickenburg, then north through Skull Valley and eventually into the Prescott Valley.

The real Doc Crosby was a military surgeon, William Dorr Crosby, who served at Fort McDowell during 1884–1886. He registered the brand but never used it because he was transferred to another military post. Crosby attended Beloit College, a small school in Beloit, Wisconsin, located in Rock County. Crosby’s brand changed hands over the years and was eventually acquired by E. O. Brown in 1917. Brown had come to Scottsdale from Janesville, Wisconsin, in 1904. Janesville is located less than seven miles north of Beloit in Rock County. Upon E. O. Brown’s death, ownership of the DC brand passed to one of his sons, E. E. Brown. E. E., needing financial support, acquired a business partner, Kemper Marley, who eventually acquired sole rights to the brand. A close associate of Marley’s was convicted of organizing the bombing assassination of Arizona Republic reporter Don Bolles in 1976. Bolles had been investigating Marley’s associations with politicians and criminal elements. The Bolles murder drew national attention to political graft in Arizona. Although Marley, a prominent Arizona businessman, was never indicted for the murder, public opinion reduced him to pariah status. As his business holdings were liquidated over the years, the DC brand eventually found its way to the development company of DC Ranch. And what of the murdered Don Bolles? He is memorialized today as an honored alumnus at his alma mater—Beloit College. In one of those strange manifestations of historical coincidence, the DC cattle brand came to be created, owned, and eventually ended, over a period of a century, while passing through the lives of three individuals from the same small county with a small private college 1700 miles from the McDowells. There’s a ghost that runs through Brown’s Ranch. It is not a cow; it’s a military road. The Stoneman Road, constructed in 1870, marked the first U.S. use of what is now Preserve land during the Westward Expansion. It was an Army supply route that ran through the pass between Brown’s Mountain and the low butte north of it. The military presence it brought allowed mining to flourish along its route from Cave Creek into the Bradshaw Mountains. It became one of the first major commercial roads in the region. Much of the road here fell out of use and disappeared with the closing of Fort McDowell in 1890. Prior to the summer of 1870, soldiers at Camp McDowell on the Verde River traveled a 175-mile route in order to reach military headquarters at Fort Whipple, near the town of Prescott. The indirect network of roads that constituted that route ran southwest from Camp McDowell, along the Salt River, through Phoenix, to Wickenburg, then north through Skull Valley and eventually into the Prescott Valley.  During the summer of 1870, brevet Major General George Stoneman ordered the development of a shorter 95-mile route between Camp McDowell and Fort Whipple. On October 1st, while inspecting troops at Camp McDowell, Stoneman decided to personally check the condition of the new military trail. At 4:00 p.m. that afternoon, he left Camp McDowell heading northwest with a dozen troops, a wagon, and a journalist. That night, the party camped near what is now the intersection of Dynamite and 136th Street The following day they reached Cave Creek. The journalist, John H. Marion, described travel over the trail as rough. Unimpressed with the desert that would eventually become the McDowell Sonoran Preserve, he described it as “poor country.” That casual disrespect must have raised the ire of the McDowell Sonoran spirits. Three years after penning his derogatory description, Marion married Flora Banghart, a young woman of considerable physical beauty. The smitten Marion described her to readers of the Prescott Miner as “God’s best gift to man…with her we hope to glide down life’s rugged pathway in a pleasant way.” In 1884, Flora glided right into the arms of the district attorney, Charles Rush, who was Marion’s best friend. The two departed the territory, abandoning their spouses and four children. Crushed, Marion devoted the remainder of his life to newspaper work and politics. In 1891, while carrying a bucket of water from his well to his house, Marion stumbled and died of a heart attack. No doubt the spirits of the McDowells had their revenge, arranging for Marion to literally kick the bucket. Evidence of either fraud or incompetence is readily available to hikers along the Gateway Loop. Those mine diggings and tailings visible to the south of the Gateway Loop are the remains of the Paradise Gold Mine. PastFinder, steward, and McDowell Mountains mining authority Larry Levy tells the tale: The promoters of the Paradise Gold Mining Company organized in Arizona in 1916 and, thereafter, went about building mining improvements, digging adits and shafts, and otherwise conducting business in an apparent effort to look like successful miners. Indeed, two of the founders were listed in the Phoenix directory of the period as being consultants, or “mining experts”. As a public company, they were allowed to sell shares of stock in their venture. The one annual report—incomplete at that—they filed with the Arizona Corporation Commission in 1919 shows they had “Amounts Capital Stock Paid Up and Invested” of $22,561.76. That was a lot of money for the time. The owners supplied their promotional information to the publisher of Mines Handbook saying they had “…2 parallel veins 300 feet apart, traceable at the surface for 3,000 feet, 45 feet wide at depth of 100 feet, and averaging about $5 in gold. Sinking shaft to 200 feet level in 1917. Stock offered to the public at 25 cents.” Beyond this, no records exist of any gold ever having been produced from this mine. Then, in 1923, and despite the earlier appearance of serious mining activity at the mine site, the Arizona Corporation Commission began legal proceedings to revoke the public company status of the Paradise Gold Mining Company for failure to file annual reports and pay fees. A Maricopa County deputy sheriff was dispatched to serve a summons on the corporate agent and officers but reported that he could not find them. Curiously, city directories from the period show some of these people living in Phoenix for years before and after this time, including the designated agent for the corporation, who also happened to have been a deputy U.S. Attorney. And so hikers along the Gateway Loop are blessed with the view of an abandoned mine that was both a myth (no gold) and a mystery (owners who disappeared, apparently in plain sight). The Lost Dog Wash area has its own curious history and mystery, beginning with the origin of its name. There is the original lost dog, of whom we know nothing—not its name, not its owner, not even its fate. The pooch from the past serves only as an apocryphal reminder of the dangers facing those who fail to obey Scottsdale Revised Code, Chapter 21, Article II, Section 21-12, Paragraph 28—requiring all dogs within the Preserve to be on a lead. The wash earned its name recently and unfortunately when, in mid-July (!!!) 2017, three hikers took a pit-bull for a late morning walk on Lost Dog Wash Trail. The Scottsdale Fire Department received an urgent call at 12:15 p.m. indicating the hikers were in “heat distress.”. By the time they reached the trio, the dog had died. The hikers were issued citations. And, thanks to human carelessness, the wash now had a real-life canine victim to justify its name.

During the summer of 1870, brevet Major General George Stoneman ordered the development of a shorter 95-mile route between Camp McDowell and Fort Whipple. On October 1st, while inspecting troops at Camp McDowell, Stoneman decided to personally check the condition of the new military trail. At 4:00 p.m. that afternoon, he left Camp McDowell heading northwest with a dozen troops, a wagon, and a journalist. That night, the party camped near what is now the intersection of Dynamite and 136th Street The following day they reached Cave Creek. The journalist, John H. Marion, described travel over the trail as rough. Unimpressed with the desert that would eventually become the McDowell Sonoran Preserve, he described it as “poor country.” That casual disrespect must have raised the ire of the McDowell Sonoran spirits. Three years after penning his derogatory description, Marion married Flora Banghart, a young woman of considerable physical beauty. The smitten Marion described her to readers of the Prescott Miner as “God’s best gift to man…with her we hope to glide down life’s rugged pathway in a pleasant way.” In 1884, Flora glided right into the arms of the district attorney, Charles Rush, who was Marion’s best friend. The two departed the territory, abandoning their spouses and four children. Crushed, Marion devoted the remainder of his life to newspaper work and politics. In 1891, while carrying a bucket of water from his well to his house, Marion stumbled and died of a heart attack. No doubt the spirits of the McDowells had their revenge, arranging for Marion to literally kick the bucket. Evidence of either fraud or incompetence is readily available to hikers along the Gateway Loop. Those mine diggings and tailings visible to the south of the Gateway Loop are the remains of the Paradise Gold Mine. PastFinder, steward, and McDowell Mountains mining authority Larry Levy tells the tale: The promoters of the Paradise Gold Mining Company organized in Arizona in 1916 and, thereafter, went about building mining improvements, digging adits and shafts, and otherwise conducting business in an apparent effort to look like successful miners. Indeed, two of the founders were listed in the Phoenix directory of the period as being consultants, or “mining experts”. As a public company, they were allowed to sell shares of stock in their venture. The one annual report—incomplete at that—they filed with the Arizona Corporation Commission in 1919 shows they had “Amounts Capital Stock Paid Up and Invested” of $22,561.76. That was a lot of money for the time. The owners supplied their promotional information to the publisher of Mines Handbook saying they had “…2 parallel veins 300 feet apart, traceable at the surface for 3,000 feet, 45 feet wide at depth of 100 feet, and averaging about $5 in gold. Sinking shaft to 200 feet level in 1917. Stock offered to the public at 25 cents.” Beyond this, no records exist of any gold ever having been produced from this mine. Then, in 1923, and despite the earlier appearance of serious mining activity at the mine site, the Arizona Corporation Commission began legal proceedings to revoke the public company status of the Paradise Gold Mining Company for failure to file annual reports and pay fees. A Maricopa County deputy sheriff was dispatched to serve a summons on the corporate agent and officers but reported that he could not find them. Curiously, city directories from the period show some of these people living in Phoenix for years before and after this time, including the designated agent for the corporation, who also happened to have been a deputy U.S. Attorney. And so hikers along the Gateway Loop are blessed with the view of an abandoned mine that was both a myth (no gold) and a mystery (owners who disappeared, apparently in plain sight). The Lost Dog Wash area has its own curious history and mystery, beginning with the origin of its name. There is the original lost dog, of whom we know nothing—not its name, not its owner, not even its fate. The pooch from the past serves only as an apocryphal reminder of the dangers facing those who fail to obey Scottsdale Revised Code, Chapter 21, Article II, Section 21-12, Paragraph 28—requiring all dogs within the Preserve to be on a lead. The wash earned its name recently and unfortunately when, in mid-July (!!!) 2017, three hikers took a pit-bull for a late morning walk on Lost Dog Wash Trail. The Scottsdale Fire Department received an urgent call at 12:15 p.m. indicating the hikers were in “heat distress.”. By the time they reached the trio, the dog had died. The hikers were issued citations. And, thanks to human carelessness, the wash now had a real-life canine victim to justify its name.  Some tragedies are tragi-comic. The 2,000-acre burned area that flanks the Lost Dog Wash Trail provides proof that no good deed will go unpunished. In 1993, a survey crew was working in Lost Dog Wash, assessing the site for a diversion dam. One of the surveyors was beset by the need of lower intestinal relief and stepped off into the desert brush to make a deposit. At the conclusion of the act, he found himself with used toilet paper. Ecologically sensitive, he decided to burn the material and, ironically, “leave no trace.” It was a breezy day. The burning paper cartwheeled along the desert floor and through its dry grasses. Two days and 2,000 charred acres later, the fire was extinguished. Officially, this burn is known as the Ancala Fire. Unofficially, local fire personnel refer to it as the TP Fire. Yup, not all mountains can be famous, but they sure can be interesting….

Some tragedies are tragi-comic. The 2,000-acre burned area that flanks the Lost Dog Wash Trail provides proof that no good deed will go unpunished. In 1993, a survey crew was working in Lost Dog Wash, assessing the site for a diversion dam. One of the surveyors was beset by the need of lower intestinal relief and stepped off into the desert brush to make a deposit. At the conclusion of the act, he found himself with used toilet paper. Ecologically sensitive, he decided to burn the material and, ironically, “leave no trace.” It was a breezy day. The burning paper cartwheeled along the desert floor and through its dry grasses. Two days and 2,000 charred acres later, the fire was extinguished. Officially, this burn is known as the Ancala Fire. Unofficially, local fire personnel refer to it as the TP Fire. Yup, not all mountains can be famous, but they sure can be interesting….