By: Jessie Dwyer

Graduate Student, Arizona State University

Last summer, the McDowell Sonoran Conservancy partnered with Dr. Jesse Lewis’ lab at Arizona State University to conduct a pilot research study on bats in the McDowell Sonoran Preserve. The goal of the study was to gain fundamental knowledge about bats by determining which Arizona bat species are present at the Preserve. Using acoustic monitoring, we detected 12 different bat species, bringing the total number of recorded plant and animal species in the McDowell Sonoran Preserve to more than 1,000. WOW!

Bats Species Detected at the McDowell Sonoran Preserve (Summer 2019)

- Western mastiff bat Eurmops perotis

- Big/Pocketed free-tailed bat Nyctinomops sp.

- Mexican free-tailed bat Tadarida brasiliensis

- Pallid Bat Antrozous pallidus

- Townsend’s big-eared bat Corynorhinus townsendii

- Western red bat Lasiurus blossevillii

- Silver-haired bat Lasionycteris noctivagans

- Western yellow bat Lasiurus xanthinus

- California myotis Myotis californicus

- Western small-footed myotis Myotis ciliolabrum

- Cave myotis Myotis velifer

- Canyon bat Parastrellus hesperus

All About Bats

Bats are mysterious, and often misunderstood, creatures of the night. So what exactly makes them so special?

For one, bats are the only mammals that have evolved true flight! Bat wings are composed of elongated hand and finger bones connected to their body by a thin, elastic membrane. The structure and function of bat wings support flight maneuverability, speed, and agility and even enables the bats to flap one wing independently of the other!

Furthermore, most bats can echolocate, meaning they can navigate with sound! Bats echolocate by emitting sounds from their mouth that bounce off objects in the environment, allowing the bat to interpret its surrounding as three-dimensional objects. Bat echolocation calls vary by species and task, such as commuting, approaching prey, or socializing.

The unique adaptations of flight and echolocation have allowed bats to survive and diversify greatly. There are more than 1,400 species of bats worldwide – 1 in 5, or 20%, of all mammals in the world, are bats! The state of Arizona has 28 species of bats, one of the highest number of species in the United States, second only to Texas.

Bats also vary greatly in traits and ecological roles between species. Species traits such as body size, wing shape, diet, and roost preference influences what habitat they use and which roles they play in an ecosystem.

Bats are important ecologically and economically and play essential roles in ecosystems around the world, such as pollinator, seed disperser, and predator of night insects. For example, aerial insectivorous bats are the largest predators of night-flying insects, a natural pest control service that saves the U.S. agriculture industry billions of dollars annually.

Bat Species Highlights

Let’s take a closer look at a few of the species we detected and what they might be up to at the McDowell Sonoran Preserve!

Mexican free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis); photo by Ann Froschauer, USFWS

Mexican free-tailed Bat:

- Large bat with long, narrow wings for fast, strong flight

- Aerial insectivore – predator of night-flying insects

- Roosts in large colonies – sometimes in the millions!

- Tolerant of artificial light

Pallid bat (Antrozous pallidus); photo by Scott Sprague

Pallid Bat:

- Broader wings for maneuverable flight, can hover to catch prey

- Gleaning insectivore – predator of ground-dwelling insects

- Immune to scorpion stings!

- Will enter torpor (temporary hibernation) during winter

Silver-haired bat (Lasiurus noctivagans); photo by Larissa Bishop-Boros (CC BY-SA)

Silver-haired Bat:

- Black hair with silver, icy tips

- Aerial insectivore – predator of night-flying insects

- Solitary, tree-roosting bat

- Long-distance migration

- One of the slowest bats in North America!

So How Exactly Do You Study Bats?

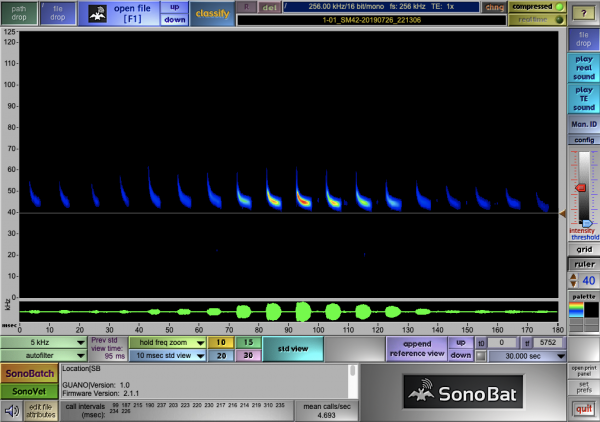

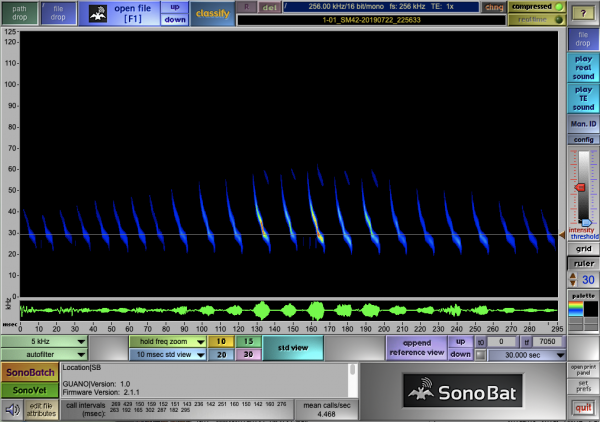

There are many research methods for studying bats, including mist netting, harp trapping, spotlighting, radio tracking, roost surveys, video monitoring, and acoustic monitoring. We used a passive monitoring technique called acoustic bat monitoring that collects data by recording the unique frequencies of bat echolocation calls (8–60 kHz in Arizona). We then used a species identification software that allows us to identify the species visually based on their identifying call characteristics, such as frequency, call shape, call duration.

Sonograms of echolocation calls from the canyon bat (Parastrellus hesperus) (left) and pallid bat (Antrozous pallidus) (right) displayed in the species identification software SonoBat 4.2.2.

McDowell Sonoran Preserve Pilot Study

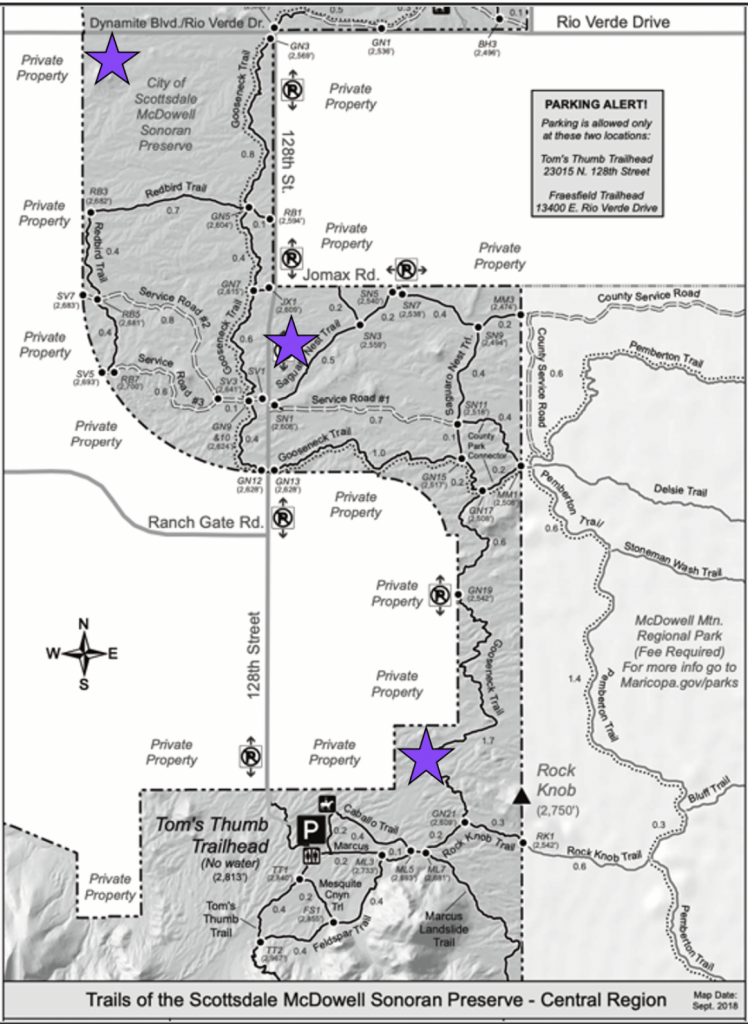

For the pilot study at the McDowell Sonoran Preserve, we used passive, stationary acoustic monitoring to survey three sites along the Gooseneck Corridor in September 2019. The acoustic monitor recorded bat echolocation calls from sunset to sunrise for two weeks. The equipment consisted of a microphone on a pole that poked out the top of a tree canopy and the bat monitor itself, which was secured to a branch within the tree canopy. The microphone was oriented to record the echolocation calls of bats flying overhead and to reduce sound interference from the environment. We confidently identified the 12 bat species listed above.

Map of the study area, the Gooseneck Corridor at the McDowell Sonoran Preserve. Monitor sites indicated by a purple star.

Acoustic bat monitor equipment. Microphone indicated by red circle and camoflaged monitor indicated by yellow circle.

Future Research on Bats in Arizona

The Lewis lab at Arizona State University, with support from the Central Arizona—Phoenix Long-term Ecological Research (CAP LTER) program, is currently researching the effect of urbanization on Arizona bat species. The different traits and behaviors of bat species influence their response to urbanization. The Mexican free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis), for example, is more tolerant of urbanization due to its large size, strong flight, tolerance of artificial light, and ability to roost in human-made structures.

Little research has been done on bats in Arizona, so research like this, as well as the pilot study at the Preserve, are essential for understanding and conserving bats as human development continues to expand.

The ultimate goal is to monitor bat populations long-term. Long-term monitoring enables researchers to detect changes in populations and act quickly if conservation efforts are needed. The more we research and understand bats, the better equipped we will be to protect their populations in this everchanging world.

Should I Be Afraid of Bats?

Like any wild animal, it is best to keep your distance from bats, for your safety and theirs. When recreating, do not disturb bat roosts and stay on designated human trails. Bats are protected under Arizona law and cannot be collected or killed. If you see a bat on the ground or in a confined space, do not attempt to handle it! Please call your local wildlife rehabilitator or game and fish department for assistance.

Misconceptions surrounding bats have persisted for thousands of years. We will breakdown a few here:

First and foremost, bats do NOT want to suck your blood! There are only three true vampire bat species out of 1,400 species worldwide. Those three species mostly prey on birds and livestock rather than humans, and they make their home in Latin America. Most bat species eat insects, fish, nectar, or fruit.

Secondly, contrary to popular belief, less than 1% of wild bats are likely to carry rabies at any given time. However, if you do get bit by a bat (or any other wild animal), contact your local county health department and game and fish department for assistance.

Additionally, there is a plethora of misinformation about bats and coronaviruses as scientists continue to investigate the true origins of COVID-19. For information on bats and COVID-19, please check out the Bat Conservation International (BCI) FAQ.

And lastly, there is a common misconception that bats are not cute, so I present the following evidence to the contrary:

Townsends big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii); photo by Scott Sprague

Roosting pallid bats (Antrozous pallidus) with pollen on their faces; photo by Scott Sprague

California leaf-nosed bat (Macrotus californicus), being shy; photo by Lynne Janney Russell

…I rest my case.

Interested in Learning More About Bats?

OK – so bats are great! How can I learn more?

- Bat Conservation International (BCI)

- Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation

- Arizona Game and Fish: Living with Bats

- Sonoran Desert Museum: Bat Facts

- Bats and White-nose Syndrome (WNS)

- Donate to the McDowell Sonoran Conservancy so research like this can continue!